Science Fiction, Ubicomp and Design.

To talk about how science fact swaps properties with science fiction, I’m going to start with Ubiquitous Computing because it is much more than just an engineering-and-computer-science-fact. Ubicomp lies somewhere in the middle of the science-fact / science-fiction continuum, which isn’t a bad thing. It’s actually a very creative, productive and exciting positioning. It’s creative and productive because Ubicomp people get to make things that have a different in-the-hand kind of tangibility than the story props of science fiction. It’s exciting because you can tell stories that are differ- ent from the sometimes boring, terse and technical instrumentalities of the normal, engineering sort of science fact.

Ubicomp is a science-fact that has snagged itself between the “here” of almost-ready-for-consumer-markets and the “out there” of near future spec- ulation. It’s somewhere between corporate sponsored research and develop- ment, and cyberpunk science fiction. Ubicomp is where you get to work on things that typically only find expression as objects from some science fiction universe. When you work in the Ubicomp field, it’s bit like being able to make science fiction fan art — all the cool technologies and concepts that you see in your favorite science fiction — only the fan art is built tech- nologies rather than sketchbook doodles or inert plastic models or wood and Styrofoam props.

In this section I reveal how the facts of Ubicomp becomes entangled with science fiction. At the same time I will show how a blurry boundary between fact and fiction can be creatively liberating, offering oppor- tunities to explore ideas that may be thought about, but rarely explored. Productively confusing science fact and science fiction may be the only way for the science of fact to reach beyond itself and achieve more than incre- mental forms of innovation. In order to do this I’ll be describing Ubicomp because it stands out as an instance of where science fact and science fiction happen simultaneously. It is therefore a good site of knowledge and culture production. It has a lot to say about design fiction practices.

Rather than describing Ubicomp through a history, or a timeline of im- portant projects, or a survey of researchers’ biographies, CVs or interviews, I will trace the contours of the field, revealing where it bumps up against science fiction. My reason for doing this is to imply that the interface where science fact and science fiction swap properties is what actually defines Ubicomp, perhaps even more than the actual technical work itself. If we look closely at some of the defining statements of Ubicomp — the words and statements and goals that describe the endeavor — we find some prop- erties that are very closely aligned with the principles of science fiction.

My second reason for describing Ubicomp by looking at the contours of the field where fact and fiction blur is to highlight precisely this property, the way in which Ubicomp activities, concepts, objects and prototypes are simultaneously fact and fiction. As science slides back and forth between fact and fiction, refusing to stick at either end for very long, the proper- ties and cultural effects of fact and fiction swap places. Fact becomes useful as a way to enliven fiction; fiction becomes a useful example and index for describing fact. Ubicomp is a good example of this because this property swapping is so continuous, acting as a kind of defining mechanism. This kind property swapping is a key feature of Ubicomp. It would be difficult to describe Ubicomp without highlighting this, as would happen if I were to describe it just in terms of its history, or just as a table of important projects, or even stories about the hard work of its researchers.

These places around Ubicomp where it hits the boundaries of science fiction are more than curiosities. They are what give Ubicomp significant, inextricable, cultural meaning. The interfaces are where Ubicomp becomes public, where it gains a kind of everyday legibility that is richer than the terse science fact of technical specifications. The interfaces between fact and fiction define Ubicomp to such an extent that there is no way to ignore, or wipe clean, or avoid the kind of imaginary flights of thought that are part- and-parcel of science fiction.

My point here is nowhere near an indictment. I am not saying — “Ubicomp, you’ve been fooling yourself into thinking that you are a kind of science fact, deserving of the accolades of that endeavor.” Rather, what I am highlighting are the benefits and virtues unique to Ubicomp as an obvious hybrid science, an enterprise that can serve as a useful model for other en- deavors.

My description of Ubicomp makes plain its relationship to science fiction so as to highlight how science fiction and science fact are knotted together into a mutually reliant assemblage. The example that comes immediately to my mind is the way many of the important principles and examples of the Ubicomp future that were pioneered at Xerox PARC find their finest, most complete expression in science fiction. This is true to such an extent that props in some stories and films like Minority Report have become the most legible indexical examples of what Ubicomp is. Science fiction serves as a richer, more complete kind of prototyping technique for Ubicomp science fact than the science fact itself.

What next? First, I will describe the core of Ubicomp through some early statements about its goals as expressed by its early thought leaders. I’ll con- sider these remarks in the context of how they’ve been expressed in science fiction. Then I will look at those two essays by Genevieve Bell and Paul Dourish that stake out a conceptual contour that puts the science fact prac- tices of Ubicomp alongside of some principles of science fiction broadly. The first essay does this by describing Ubicomp’s relationship to the “near future”, an important conceptual frame for a style of science fiction. The second essay looks more directly at a kind of cultural legacy which traces many Ubicomp conceptual principles and ideologies back to science fiction television of the 1970s and 1980s.

Xerox PARC is often credited as the canonical emergence of Ubicomp, this happening around 1988 with the formation of The Ubiquitous Computing program there. As described by early researchers at PARC, Ubicomp was meant to address some of the broad, systemic problems with computers at the time, and which continue to linger to this day.

“The program was at first envisioned as a radical answer to what was wrong with the personal computer: too complex and hard to use; too de- manding of attention; too isolating from other people and activities; and too dominating as it colonized our desktops and our lives.

“We wanted to put computing back in its place, to reposition it into the environmental background, to concentrate on human-to-human interfaces and less on human-to-computer ones. By 1992, when our first experimen- tal “ubi-comp” system was being implemented, we came to realize that we were, in fact, actually redefining the entire relationship of humans, work, and technology for the post-PC era.”

What the Ubicomp researchers were involving themselves with was a whole new category of human-computer interface. They weren’t improving keyboards to make them more ergonomic so they would cause less repetitive stress syndrome. Nor were they making computer mice with better tracking so they wouldn’t get hung up on the dust and lint on your desk. Their focus was much broader in that they set upon the task of completely changing the interaction rituals one engaged in while “computing.” Even the computer mouse — itself a profound world-changing innovation developed at the same research center — was something they were looking to move beyond. A desk cluttered with a keyboard, mouse and video display — the canoni- cal “keyboard/video/mouse” interaction framework — was old school in the near future imaginary of Ubicomp, right from the start. Although at this time — the late 1980s — this setup of keyboard/video/mouse was drawing more and more of a lay public into the world of computing, Ubicomp was looking to create the computer for the near future — a computer for the “post-PC era.” The question was — what would computing look like in the 21st century?

What was envisioned was a wholesale shift in the means and even goals of networked computer technology. As a core principle, the Ubicomp imagi- nary sets out to develop technologies that are adapted to the ways humans interact with humans, rather than assemblages of technologies in which humans are shackled to the computer. The PC imposes constraints from

the Ubicomp point of view — constraints by virtue of its size and weight, the way we are forced to sit down in front of it and stare at its flat screen, and hook our fingers over little plastic squares in order to “interact natu- rally.” Computing should not be about the needs and demands of the com- puter itself. From the beginning, design of computing practices should take into account the ways humans occupy, socialize and move in the world. According to Weiser, these issues outlined some of the contours of Ubicomp — a “next generation computing environment in which each person is con- tinually interacting with hundreds of nearby wirelessly interconnected com- puters.”

It is particularly fitting that such a grand vision for a largely technical endeavor find unique expression in science fiction. Consider these themes in relationship to the Minority Report gesture interface, particularly in the context of whatever you may imagine a post-desktop/laptop-PC era may be in which our relationship between ourselves and our work — for example, manipulating lots of digital media content somehow brought backward in time from the future.

Imagining what an entire redefinition of such things might entail can happen in a number of ways, only one of which is the hard, studied, intense work of brilliant scientists, anthropologists, designers and artists working on Ubicomp at Xerox PARC in the decades following the 1980s. We might also reasonable hope that the fun, hard work of imagining a near future world can be explored through many other approaches to idea materialization, not just the techniques of science fact production. We might reason- ably wonder how science fiction re-imagines today’s style of computing and interaction design in a world tomorrow, where there are ubiquitous net- works of connected sensors and other, new, yet-to-be imagined kinds of interaction rituals. And we might also wonder about the larger social context of that future world, from the profound to the everyday. What do people in the future do, absent their supposed need for next generation microproces- sors, retinal scanning sensors, RFID credit cards, biometric car keys, robot vacuum cleaners or WiFi-enabled bread makers? Is the world friendly or scary? Do people trust one another? How’s the weather? Are ice cubes more valuable than gold? Has phoning someone up become as vintage as sending email or throwing sheep? How does science fiction imagine what science fact has posited as possible vectors of research and fill out the context of human social life? What lives beyond the props? What are the stories that make up the world? How does a Ubicomp world “fill out” in its broader context? Can science fiction help imagine, extending the probable as well as highly spec- ulative conclusions to Ubicomp research? Can it effectively prototype the concepts of Ubicomp by exploring, extending, hypothesizing, speculating through visual stories, for example, as one might find in science fiction film?

We might imagine that the best Ubicomp research has occurred in science fiction by virtue of the ability of its stories to speculate and bring to life the Ubicomp worlds that may come to be. Moreover, science fiction not only imagines the context of the Ubicomp future, it presents possible conse- quences, implications and the inevitable failures of technologies to close the gap between the pitchman’s hype and the actual experience. Science fiction prototypes the concepts.

Consider my favorite example (there are many more that I’m sure any sci- ence-fiction fan can conjure) of the Minority Report scene described earlier. It presents a prototype — a diegetic prototype as described in the previous section, to use David A. Kirby’s terms — of a kind of gesture-based interface technique for interacting with media elements. It’s a rather complete con- ceptualization of what would go into such an interaction ritual. It includes a “language” of gestures rather well considered by the technical consultant/ engineer John Underkoffler that is consistent with the actions that the char- acter is performing. The design suggests the use of a reasonable, glove-and- light tracking technology, and so forth.

Further examples in Minority Report work through some of the other ca- nonical, gold-standard concepts often discussed and puzzled over from the Ubicomp future imaginary. There is a web of ubiquitous, networked com- puters in the forms of sensors and displays “seamlessly” integrated into the fabric of the normal, human built environment. We see this in the form of holographic advertisements found in the scenes where the John Anderton character is attempting to evade pursuing police. In this future, the Ubicomp world has greeters personalized to your database/life experiences, who pop-up into view after they’ve unobtrusively scanned your retina. The Ubicomp future imaginary in Minority Report has no annoying kiosk to type at in order to login to a shopping mall either online or in the bricks- and-mortar built environment. There’s no need to remember usernames and passwords — they’re all indexed to the unique biology of the pattern of veins on your very own retina.

Examples of the Ubicomp vision can be found in countless other science fiction examples. The recent Batman interpretation, The Dark Knight, shows the morally challenging possibilities of using everyone’s cell phones as a massive, world-blanketing listening, audio sensor grid that, just like a ship’s sonar, is able to create a three-dimensional map of the world.

Beyond imagining the possibilities of a near future world of ubiquitous computing style interactions, science fiction does science fact better than science fact in at least one aspect of its work. In what way might visual story tellers, technical consultants, props makers and science fiction authors be doing Ubicomp research and, perhaps, doing it better than their Ph.D. counterparts working studiously in their labs? They tell a better story because they are story tellers, because they understand that a technical in- strument lives in a social world, whereas an engineer will tend to constrain the context to instrumental functionality.

A better story can make a world of difference, especially if the world is more likely to pay attention and share their insights and further circulate the knowledge, principles and perspectives on what such a future might be like. The engineer-scientist-researcher’s story is often muddled and tech- nical and these kinds of “stories” — really narratives about operational nuances — only circulate amongst a few thousand of their peers, many of whom don’t bother to read their colleagues papers anyway. It is the princi- ple of circulating knowledge that is at the core of the science fact enterprise, and it could do a better job of this. The connected graphs of citation tend to cluster and cycle and clump. Science is what it is by virtue of its ability to disseminate, argue about and share knowledge. Without that, science is only smart people sitting in a laboratory, sharing only amongst themselves, with no points of entry to disseminate their insights and the sense of what possible new worlds may derive based on their work. All science is only ever potential. Without the ability to create a meaningful, human dimen- sion to the work, to have it enter upon the world and create stories in which humans and their lives figure centrally — there is nothing more than ab- stractions that probably do not make much sense to those who need to be told a story about how life could be in order to give the knowledge relevance and meaning.

The science fiction film is arguably much more effective than the more generally understood way of creating and sharing scientific knowledge, peer review protocols notwithstanding. The film adds a kind of idea-mass to something like Ubicomp that spreads the story much further, gives it more meaning in the context of a reasonable, non-ideal, flawed, human social world and does so with more momentum than a dowdy paper in an obscure, difficult to find science journal that, at best, comes up with scenar- ios that are about as realistic as a laptop that never crashes or wireless phone networks that never drop calls. The Ubicomp science fiction can bring to light consequences, conclusions and implications much better than a science fact paper, or awkward laboratory demonstration.

Can you imagine explaining a Ubicomp gestural interface to a layperson used to the conventions of the canonical trinity of keyboard-video-mouse, without a story to help fill-in the broader, inevitable question of — why would anyone want this? Of what use might it be? Might not it be helpful to show a bit of Minority Report? You could say “Hold on, let me show you

a little bit of what I’m imagining; it’s science fiction, but still — I think it will help give your imagination a bit of an anchor, it will help explain what I am talking about. If you watch this, we will have a bit of shared, fictional imagi- nary space in which we can continue our conversation about this thing — this weird thing — that I am thinking about.” It makes me think that any good scientist should also be particularly good at science fiction, maybe even better than they are at science fact. While we’re on this point, imagine how science fiction could be part of a better science and engineering curriculum, despite what the official curriculum sanctioning boards say.

Through this example, we can see how Philip K. Dick, Spielberg and Cruise together with a team of prop designers and technical consultants may actually be doing better Ubicomp than Ubicomp researchers at univer- sity and corporate research labs do themselves. In fact, it is the case that P.K. Dick, Spielberg and Cruise are Ubicomp researchers, they just don’t know it.

From a blog post on near future science fiction found on “Charlie’s Diary” which describes near future science fiction as a genre of science fiction that creates linkages between “now” and an imagined, speculative “then” through compelling associations and extrapolations of existing tech- noscience.

“What is near future SF?

I’m prompted to write this entry simply because a number of folks on the earlier blog entry seem to have misunderstood the point I was making … this is by way of illumination.

In my view, near future SF isn’t SF set n years in the future. Rather, it’s SF that connects to the reader’s life: SF about times we, personally, can con- ceive of living through (barring illness or old age). It’s SF that delivers a powerful message — this is where you are going. As such, it’s almost the diametric opposite of a utopian work; utopias are an unattainable perfection, but good near future SF strive for realism.

Orwell’s 1984 wasn’t written as near future SF, even though he wrote it in 1948, a mere 36 years out: it explicitly posits a global dislocation, a nuclear war and a total upheaval, between the world inhabited by Orwell’s readers and the world of Winston Smith. You can’t get there from here, because it’s a parable and a dystopian warning: the world of Ingsoc is not for you.

In contrast, Bruce Sterling’s Holy Fire is near future SF, even though it’s set nearly a century out; his heroine, a centenarian survivor from our own times, is on the receiving end of a new anti-aging medical treatment that has some odd side-effects, and so we get a chance to tour the late 21st century vicariously. You’re meant to think, “I could end up there” — that’s the whole point of near future SF.

Technothrillers aren’t near future SF. Technothrillers are thrillers first; they play against the background of the world as we know it (albeit the world of drama and espionage and public affairs) without considering the way the technology trappings they rely on might change the human condition. The high-tech stuff is window dressing.

Near future SF does different things with the same tools; they come front-and-centre — or rather, their effects come front-and-centre, and the world is changed thereby. And they’re not necessarily such obvious new technologies as smart bombs and wrist-watch radios; they might equally well be a new way of looking at the memetic spread of fashions, as in Connie Willis’ Belwether, or social network mediated economics, as in Bruce Sterling’s Maneki Neko.”

Posted by Charlie Stross on October 2, 2008 2:14 PM on “Charlie’s Diary”

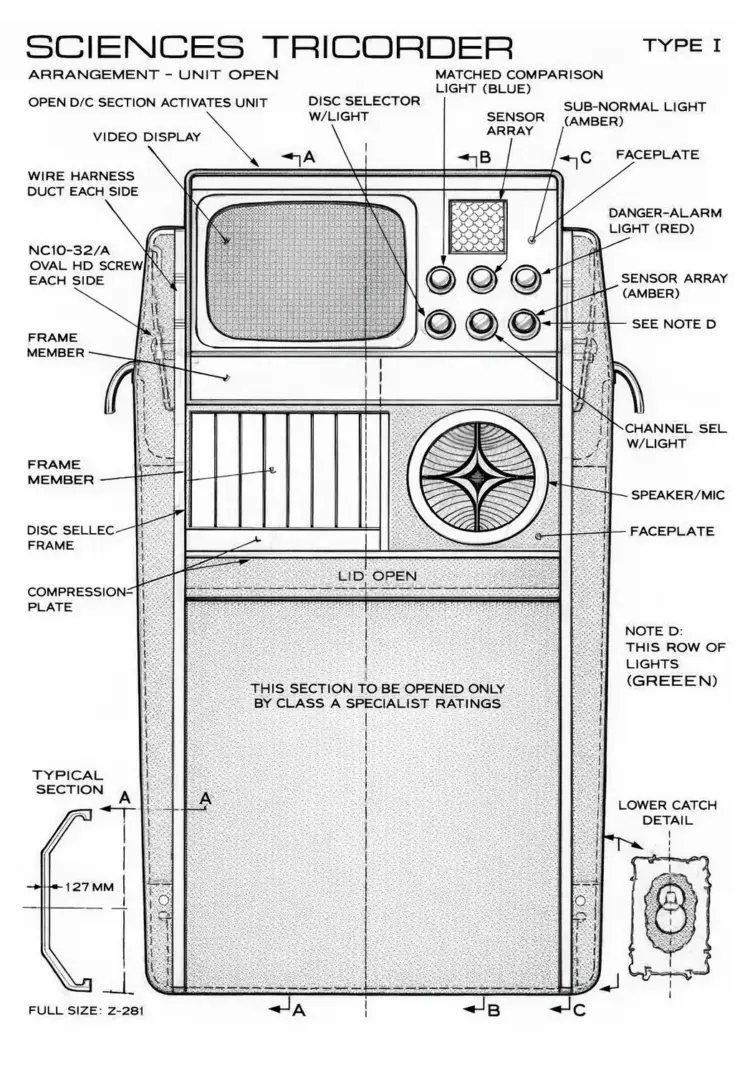

Fan art evolved to the point of speculating about the technical particulars of props from science fiction is found in this diagram from The Star Trek Star Fleet Technical Manual, by Franz Joseph, a technical artist and designer who worked during the day for General Dynamics.

Joseph expressed his creative skills in speculative technical schematics, design documents and blueprints of Star Trek ships, clothing, instru- ments, weapons and control panels. The material proved exceptionally popular amongst fans, providing an additional point of entry for enjoying the science fictional world of Star Trek. His book is a kind of false docu- ment — one that turns the science fiction into a future science fact.

Even more intriguing, and another instance of border crossing that can occur when imagined worlds meet material worlds, is that the creative ex- plorations in Joseph’s works made their way back into the science fiction. His imaginary material became used as new props, backdrops and exten- sions of the technical and engineering principles of the science fiction.

Joseph’s technical fan art translates the science fiction into a kind of science fact to the extent that he considers the materialization of the various artefacts. Patterns are given for constructing the Star Fleet uni- forms worn within the science fiction. Architectural diagrams are drafted for the space ships. Regulation patterns for fleet colors and banners are specified. Organization charts for command and operational hierarchies are mapped out. There are design schematics for technologies that only exist in the science fiction.

This would be fandom taken to fanatical degrees unless you consider this in today’s networked culture context. Plainly, this is “user-generated content” before there was such a broad sensibility about the meaning of such a thing. And this kind of expression is an important, albeit curious form of fact and fiction swapping properties, with unexpected outcomes. If nothing else, we can infer from this example the willfulness of people to express more completely the science fiction. We cannot anticipate the potential of this will to contribute to and circulate new cultural forms. For example, some of Joseph’s material found its way into the science fiction as props in the show itself, including star ships he designed that, originally, when he drew them, were not part of the Star Trek science fiction world.

Anecdotally, Joseph’s self-made Technical Manual, done without prompt- ing by The Star Trek producers but with their encouragement, was very popular as indicated by its status as a New York Times best selling trade paperback (December 1976.) This may have prompted Paramount to consider reviving the franchise after its initial very short run.

A science fiction film will not necessarily tell you a whole lot about Ubicomp as a field of knowledge production, although it can do a great job of imagining what Ubicomp in the world of human social practices becomes, and not just the ideal fantasy world that never comes to fruition — the one the marketing people tell of seamless, perfect internet connec- tions and spotless kitchen counters. The science fiction film can do a better job of imagining the Ubicomp future than Ubicomp can imagine for itself. To find out what Ubicomp is from the perspective of the non film-making, science fact practitioners means turning to one of the Ubicomp knowledge circulating mechanisms, the academic journal. In this case, you might pick the journal “Personal and Ubiquitous Computing” — one of the more pres- tigious journals in the Ubicomp field. It will cost you dearly to find out about Ubicomp from ubiquitous computing professionals. You’ll shell out over $1,100 for a year’s subscription to that journal. That’s 8 issues. That’s definitely more than the price of admission for a science fiction film, or the cost of a Philip K. Dick book, or a subscription to a good science fiction quarterly, any of which will almost certainly have more good Ubicomp in them than one volume of that stodgy, expensive academic journal.

Maybe you have access to Personal and Ubiquitous Computing through your job, or you’re a student at a university with a subscription, or your local public library system is particularly recession proof and fast-and-loose with its periodicals budget. In these cases, you can participate in the science fact of Ubicomp. But the obvious irony is that the science facts of ubiquitous computing knowledge are hardly ubiquitous. For most people who watch a science fiction film like Minority Report, I would guess that the dominant near future imaginary for networked computation is disrupted more power- fully through the film’s story than the conventional scientific paper publish- ing mechanism of circulating new ideas about digital technology. Such need not be ironic. It should be a matter of course, a routine aspect of how new ideas come into being. This can be the case if we allow for productive, cre- ative, undisciplinary entanglements of science fact and science fiction, with no primacy over who or what gets to matter most in the act of making the future.

In some ways science fiction is the core DNA of Ubicomp, coming as it does from the underlying assumptions and motivations laid out in the early statements as to Ubicomp’s goals. In what follows, I’d like to explore the notion that Ubicomp always has had a relationship to science fiction in a productive, fruitful way. Certain of Ubicomp’s properties indicate that it is in-between science fact and science fiction. It is a kind of science fact that is also at the same time a kind of science fiction. In particular there are two properties to highlight. The first is the way Ubicomp imagines the future it aspires to and constructs through its projects. Second are some of the important themes and central concerns that exist in its shared imaginary, many of which also find expression in science fiction proper.

I didn’t come up with these two properties on my own. I read them in a pair of essays by two scientists from the Ubicomp field wrote over the years. Paul Dourish is a computer scientist, and Genevieve Bell is an an- thropologist. They’ve worked at places like Xerox PARC and Intel and the University of California, so they know what they’re talking about. They’ve done Ubicomp from a number of angles. Ubicomp is a practical matter for them — something to be constructed — as well as something to be studied in itself and to be understood as an endeavor of human beings intent on creating a particular near future technoculture. Two essays they’ve written together capture these properties well, and do so in a way that allows us to draw together some conclusions about design fiction. The essays create an extended contour around Ubicomp that is a reflective account of Ubicomp itself, rather than a technical article or project write-up.

The first essay I’m referring to was published in 2006 in that expensive journal — Personal and Ubiquitous Computing. It is titled “Yesterday’s to- morrows: Notes on ubiquitous computing’s dominant vision.” I was able to get it because I’ve managed to get access to those expensive journals through the various jobs in and out of academia I have had. This one essay says about as much about Ubicomp and what it is as we’ll need for the time being, so this is where we’ll start. It provides an entry point into the knot that ties science fact to science fiction and, in that messy entanglement, in the act of the knotting together, describes what I mean by design fiction. Their point in this essay is to consider that Ubicomp has always been about a future per- petually deferred. Ubicomp has from the start been about the near future. The Ubicomp world is one imagined to be a few years from now, which is an unusual principle for a science fact. So unusual that it is perhaps more closely aligned with near future science fiction than it is with other boring old pragmatic engineering-style science fact.

The second essay is called “’Resistance is Futile’: Reading Science Fiction Alongside Ubiquitous Computing.” You can find it in that same expensive journal. This essay does something quite bold in that it looks at the collec- tive imagination of the Ubicomp field (scientists, researchers, and so on but, curiously, not its objects and props and prototypes) alongside of the science fiction imaginary as seen through a number of science fiction shows that are arguably part of the shared history of Ubicomp researchers. By itself, this topic is intriguing, first because it is not typical for a technical journal to publish a reflection of this sort — one that draws more from humanities in its approach and argument than from the idiom of the technical paper. But, more importantly in the context of design fiction is their argument that the narrative themes and cultural implications within the science fiction stories are properties that participate in design practices whether you like it or not. These themes are only in science fiction in their examples because they are largely ignored and considered irrelevant in most technological design practices. But allowing these themes to “participate” in technological design has value to the design practice and its methodology.

The purpose of sketching this very brief two-point contour of Ubicomp

is to describe it as an instance of how science fact can usefully behave as science fiction, drawing from the frankly more liberating, innovative means of turning ideas into material than most conservative, rational, level-headed, markets-driven science fact is able. It takes some steady nerves to let go of convention and expectations about how the future looks, the direction to which progress is meant to go, constructively imagining that there are mul- tiple possible futures rather than one future that goes in one direction (up and to the right), or one future, evenly distributed. Rather than pursuing science under the old assumptions about the singularity of facts, why not a bit of engagement with speculation that wraps an imaginable world around some props, prototypes of ideas and a few conversation pieces that help tell a larger story about the world in which you might live, in the near future.

In “Yesterday’s tomorrows” Bell and Dourish describe Ubicomp as an endlessly deferred vision of technology for the future. They reach back to the defining essay on the topic, written by Ubicomp’s avuncular visionary, thought-leader and one of its founding scientists, Marc Weiser.

Weiser set out a vision of the future through what he called “the computer of the 21st century.” Bell and Dourish ask themselves: what does it do to this unusual technology enterprise to base its endeavors on a vision of the future, when most technology enterprises base their endeavors on a problem rooted in the past that is meant to be overcome in the future through the hard work and tireless efforts of science and technology? In their words:

“Most areas of computer science research..are defined largely by techni- cal problems, and driven by building upon and elaborating a body of past results. Ubiquitous computing, by contrast, encompasses a wide range of disparate technological areas brought together by a focus upon a common vision. It is driven, then, not so much by the problems of the past but by the possibilities of the future.”

The dilemma that arises is that this shared vision first expressed by Weiser and then taken up in full-force by Ubicomp scientists internationally had this explicit deadline of sorts: the computer for the 21st century. After more than a decade and, now, snug in the 21st century, Dourish and Bell point out that, “We now inhabit the future imagined by [the Ubicomp pioneers]. The future, though, may not have worked out as the field collectively imag- ined.”

The point that the computer for the 21st century as described by Weiser has yet to come into existence, or that the computer for the 21st century still looks very much like the computer for the 20th century is not a reason to dismiss Ubicomp, of course. It was not that Ubicomp necessarily expected to achieve a specific deadline and make this thing that was living in a shared imagination. Ubicomp set a specific goal which may have been rea- sonable as a set of parameters for a speculative design of the near future of computation. It was as if Weiser’s visionary statement is saying “The ideas developed here, in our labs, are what we imagine to be pervasive, mass-market, vernacular experiences in a couple of decades. This is how we’ll work together, to make this entirely possible near future.”

This notion of a “proximate future” as Dourish and Bell describe it, is an aspirational future, a near future imaginary. This is an important property of Ubicomp, and a reason why it should not be taken too literally, otherwise you may miss its most important property. It is as if Ubicomp is less about creating technologies than it is about creating materialized idea-objects that are, in some way, from or for the near future. It is as much about doing re- search in laboratories as it is about a dramatically different future in the act of being created. But there’s more. Ubicomp “imagines” in a way that allows it more than a usual amount of leeway to consider future worlds, even spec- ulate about peculiar corners of that future.

This is Ubicomp’s curious relationship to the future. Effectively it is working on the future in a way that most other technology enterprises are not able to do, or in fact are not allowed to do. Speculating about possible futures is a relatively dangerous thing for science-fact to do. After all, it could come out wrong. Most science-fact works under the assumption that there are facts out there to be revealed and, with enough time, this revela- tion will come to pass. There is a combination of chemistry and mechanics that will create a battery that lasts longer than the batteries of today. It might include a mix of dried oats, corn syrup and naphthalene, but with enough time and energy and commitment, a new battery chemistry will be found that lasts 5% longer and weighs 5% less. That is the incremental approach. Quite conservative, safe, necessary to certain models of economic growth — and rather boring. On the other hand, Ubicomp seeks to achieve wholesale changes in how humans and computers worked together.

The combination of a “proximate future” and radical, wholesale changes in the way computation and humanity are tied together is bound to create difficulties in the path from imagination to materialization. Whatever the idea of a “proximate future” for Ubicomp might be by example, it works on a future endlessly deferred, always off on the horizon. It is a kind of future that is only ever imagined. It never quite becomes material form in the same way as that of those guys working hard to make laptop batteries that last 5% longer.

Incremental adjustments are boring because they are possible to imagine as logistical exercises, however painful and costly these may be. The whole- sale change is different from a future that is assumed will come to be with enough funding and time and computer workstations and graduate students to run tedious all-night experiments.

By contrast is the Ubicomp future, one that is imagined and discussed through speculative prototypes, unexpected and peculiar interaction rituals and imaginative devices and enabled objects. In an unspoken way Ubicomp is a science created to encourage conversations about possible futures through objects that speculate, not possible futures based on objects that can be manufactured. It is a very different future, much different than the kind of logistical future that many technical enterprises use as their vision of how things will come to be. In effect, Ubicomp is a kind of fiction, working with and through science to project possible near future worlds. It is not a materially substantiated future. In fact, it is a future that can only be effectively represented as science fiction.

Another important essay that Dourish and Bell wrote more recently is called “’Resistance is Futile’: Reading Science Fiction Alongside Ubiquitous Computing.” The essay starts with the premise that any kind of research enterprise such as Ubicomp that has elements of exploratory design associated with it is going to be engaged in some sort collective imagining. But collective amongst whom? Ubicomp, despite being a technical enterprise, is quite interdisciplinary. Not only within the technical practices but also beyond. There are pretty serious an- thropologists and other social scientists working alongside of equally serious hardware engineers. There are even some artists who work exclusively with technology as their expressive medium who participate in the Ubicomp field. With such a mix of backgrounds, approaches to knowledge making, disciplinary quirks, assumptions about what is and is not valid, useful or meaningful — what could a shared imaginary be? What are the collective visions of this endlessly deferred future that serve as an index for their work? What do Ubicomp researchers point to and draw from in order to describe the ideas they imagine, but have not yet materialized? If Ubicomp is about

a proximate, near future, what ties these researchers together and points to that shared future? What gives them a common set of goals, aspirations, language and a sense of community?

Bell and Dourish point out that science fiction, particularly in a popular form, can offer a way to understand the potential and possibilities of emerg- ing technologies, or even imagine possibilities that have not yet been formalized through conventional science. They orient science fiction, par- ticularly television science fiction from the 1970s, in such a way as to offer a hint at a possible point of commonality. Science fiction imagines possible future worlds. This stake in imagining the future is something also held by Ubicomp, mostly clearly as articulated by the early Ubicomp objectives as they describe in the earlier essay “Yesterday’s Tomorrows.” It makes sense then to look at science fiction alongside of Ubicomp in order to more fully explore some broad themes that undergird Ubicomp and give it some of the important characteristics of its shared imaginary.

In “Resistance is Futile” Bell and Dourish situate Ubicomp alongside five examples of science fiction that they present as some patches of common ground for a Ubicomp collective imaginary. The science fiction they offer are five visual stories that became popular through television and film. I’ll list them here. They are: Dr. Who, Star Trek, Planet of the Apes, Blake’s 7 and Hitch-Hikers Guide to the Galaxy. These are five television shows that we might imagine to form part of the cultural history of Ubicomp researchers. Or, for younger researchers, they will have an awareness of these shows to one degree or another, perhaps through re-runs, or sequels to, for example, Star Trek or the modern rendering of Hitch-Hikers Guide to the Galaxy.

Through these shows Bell and Dourish look at broad themes — bureau- cracy, technological breakdown, frontier and empire — within the science fictions by briefly addressing how the themes are presented as part of the narrative and drama. This is their set up to explore the parallels to ubiqui- tous computing research, which, like science fiction, considers the larger cul- tural contexts into which its imagined technologies will be entangled.

“..we are interested in the ways in which science fiction – the literary fig- uring of future technologies rather than the practical figuring of much con- temporary research – engages with a series of questions about the social and cultural contexts of technology use that help us reflect upon assumptions within technological research.”

Their essay is not meant to be an exhaustive analysis of science fiction and Ubicomp. It provides a few insights about science fiction and Ubicomp, using these to describe the larger, more exciting suggestions I read within the essay which is that science fiction can be a first-class participant in the design process. The specifics of each science fiction show are intriguing in and of themselves. For instance, the frontier sensibilities of Star Trek and the way this runs counter to the bureaucracy that the Enterprise has left behind in its exploration of the hinterlands of the universe. This leaves us with a story that is as much about independence and as it is about highly techno- logical space exploration. The two — technology and “rugged individualism and independence” — can go hand-in-hand, a mythos not always consistent with another popular conceptualizations of technology as a domineering, soul-crushing force.

Culture “embeds”, as it always must. There is no pure instrumentality in technologies, or sciences for that matter. The arrival of an idea, or concept, or scientific “law” comes from somewhere, never “out there” but always rather close to home. Bell and Dourish are telling us this in their essay using the particular example of Ubicomp. Ubicomp endures its own cultural spec- ificity and debt to things like desire for specific near futures that are given an aspiration portrait in, first of all, the imaginative vision of Mark Weiser and, second of all, some good old fashioned near future science fiction. They are both techniques for connecting the dots between dreams, the imagination, ideas and their materialization as “shows” that talk about the future, exhibit artifacts and prototypes. Those “shows” can take the form of a television production, film, laboratory activity, research reports, annual gatherings of die-hard fans at Ubicomp conferences and Star Trek conventions, and so on. They’re all swirling conversations that are expressions of a will, desire, cre- ativity and materiality around some shared imaginaries.

Bell and Dourish are not saying this directly, of course. I am making broader but perhaps more incisive claims about the activities by which culture happens in Ubicomp. I am using their insights about the culture of science fiction and the ways in which it finds its way into Ubicomp first principles. Effectively I’m saying that knowledge and ideas and material are circulate in a productive, engaging way across practices in an undisciplined, highly volatile and engaging way. The point is this: imagining the future of computers, different from today, and the pathways toward that goal are illu- minated in good measure by the visions and imaginations of science fiction as much as they are by the desperately pragmatic activities of things like Ubicomp.

Bell and Dourish are reminding us that the implications of culture are not something that happens after design. They are always part of the design. They are always simultaneous with the activity of making things. The culture happens as the design does. This is in every way what design is about. It is less about surfaces and detailing, and perhaps only about making culture. By making culture I mean that things-designed become part of the fabric of our lives, shaping, diffracting, knitting together our relations between the other people and objects around us. Making culture is something that en- gineering has so effectively and, at times, dangerously pushed out of view, which is why design should participate more actively and conscientiously in the making of things. Engineering tends to start with specifications, assum- ing that terse instrumentalities and operating parameters evacuate the cul- tural implications. Design brings culture deliberately. It’s already there, this culture thing — design is just able to provide the language and idioms of culture, a language which engineering has long ago forgotten.

Social or cultural “issues” or “implications” are always already part of the context for design. These are not issues that arise from a technical object once it is delivered to people, as if this act of putting an object in some- one’s hands then somehow magically transforms it into something that, now set loose to circulate in the wild cultural landscape, produces “issues” or creates implications. It is the case that the social or cultural questions are always already part of the operational procedures of the engineering work, never separate. One need only look at specifications and read closer than the surface to see where an how “culture” is the technical instrument. Despite the fact that it looks like a bunch of circuits and lifeless plastic bits, there is culture right there.

Bell and Dourish point out that:

“Wittgenstein argued that to imagine a language is to imagine a form of life; we might make the same observation about imagining technologies. Cultural questions, then are prior to, not consequent to, design practice. The kinds of questions we have raised then are not, we would argue, remote ones that we have yet to encounter; they are ones to which..we have already committed ourselves.”

They are saying that, no matter what — cultural questions are always already present, so why not actively engage them as such, and not as “issues” or “problems” to be addressed, but as useful, core aspects of the design process. The topics Bell and Dourish chose to emphasize that surround their science fiction examples are only a few of the cultural issues that are often ignored or considered outside of the realm of design. They are also big topics, and we might also wonder about the quotidian, speculating about more tactical issues in design speculations. Regardless of the level of con- sideration, these cultural questions are core to any story about life lived, as much as they are core to any design practice, whether you like it or not. It’s not enough to stop at the surface of a designed object. You have to put it in someone’s hand, imagine it’s everyday, from the fantastic possibilities to the mundane annoyances. Design is more than specifications.

A conclusion to this point might be to consider elevating science fiction, to that of a deliberate resource, a mechanism or approach as one might employ any design resource, and do so in order to consider the culture questions that are not always done particularly well with the technical in- struments and techniques used to construct technologies. Rather than something separate from the conventional methodologies of technological design, employ science fiction in order to engage in a design practice that can examine and discuss the properties, consequences and ideological stakes of emerging ideas at the point in which they begin to take on material form? That is — use science fiction as a deliberate, overt way of re-investing culture into the process of making things, particularly the kinds of things one finds in a networked world. Just as one may involve a crackerjack data structures and algorithms jockey, or an adept wireless electronics guru who can help address that thorny design issue of getting your network card to meet FCC certification standards, why not a provocative design fiction vi- sionary that can help fashion the near future imaginary in which the emerg- ing design lives. What is the world like? How is it shaped by this or that user interface speculation or a hypothetical social ritual?

The design fiction role is not a superfluous role in the design team, some- thing to be done with extra budget, or if time permits. Rather, it is as signif- icant as the guy doing the FCC certifications, as vital as the CAD software that participates in creating the tooling specifications. The design fiction role is crucial to achieving the goals and meeting the aspirations of the emerging ideas as much as any other first-class participant in the design process. Its failure is the failure to imagine what the idea and its materialization become, not only as an object by itself, but an object that participates and becomes socialized when it falls into the background and becomes a “prop” through which people’s lives are lived, really. Not the seamless perfect lives that are unimaginatively pitched through the object’s advertisements — the one’s that entice us to participate in the uninspired fiction of the sales and mar- keting teams. But that object, when it achieves its low points as well as its high points, it’s liberating benefits to free us from life’s hassles as well as its dire consequences and points of failure.

Rather than seeing objects as non-social bits of chemistry and circuitry, for example, imagine them as they are — as enablers of social relations and facilitators of social interaction rituals. What Bell and Dourish emphasize is that the cultural “implications”, which are often considered to be something that arises later, after the soldering and breadboarding and clean-room work is done and the thing is tooled, manufactured, packaged and sold — these are always already part of the technological design work. So, allow these issues to participate as part of the design practice. There is no easy way to insert these quotidian into the design practice without speculating. It’s not a software module or algorithm, it’s a story told. Science fiction can do this well, so why not start there, as a hybrid of design, science, fact and fiction.